PHYSICAL MODELING

For over 150 years, scientific experimentation has been a central method in hydraulic engineering and river research to investigate hydraulic and river engineering questions using (scaled) models under controlled conditions. The scaling is based on model laws and similarity principles.

Typical application-oriented questions range from the design of stilling basins and flood relief structures to more complex studies of morphological developments in rivers, such as river widening, and even ecohydraulic topics. These include the development of fish passage facilities or the analysis of the impact of vegetation during flood events.

The greatest advantage of a physical experiment compared to a numerical simulation is the ability to study real flow conditions without requiring the physical processes of interest to be fully described by mathematical formulas. This is particularly relevant for fundamental research questions, where the goal is to develop an understanding of processes that are not yet well understood.

Large-scale models

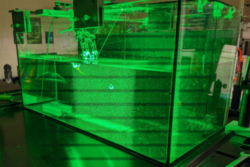

The new hydraulic engineering laboratory now enables large-scale experiments, up to a 1:1 scale. With flow rates of up to 10 m³/s and extensive indoor and outdoor facilities, the infrastructure allows for the accurate scaling of objects such as vegetation, fish, or even humans.

Another key advantage is the ability to model the full range of heterogeneous sediments found in a river without reducing the grain size. This avoids alterations to the physical properties of the sediments that would occur with downsizing. As a result, (nearly) 1:1 experiments can be conducted with Reynolds numbers that match the conditions of natural rivers. This opens new possibilities for realistic experiments and more precise insights into hydraulic engineering and river research.

Full-scale models

Full-scale models involve the comprehensive representation of the river section under investigation. The river course is replicated with its bends, riverbanks, floodplains, and any hydraulic structures or installations. This allows for the realistic reproduction of secondary flows, which play a crucial role in river bends, as well as the complex three-dimensional flows that occur when structures are bypassed or overtopped.

Full-scale models of large rivers or long river sections require significant space. In such cases, the scale often has to be very small, which can lead to scaling errors due to the significantly underestimated Reynolds number in the scaled model. Full-scale models are particularly indispensable when studying morphological developments, such as those occurring in river widenings or in areas with highly variable river geometries.

Section models

In cases where the geometry of the river can be neglected due to the dominance of relevant local properties, so-called section models are used. These typically involve modeling a “strip” of the river in the longitudinal direction. This approach allows for the construction of models at larger scales. Section models are usually built in existing laboratory flumes, making them easier to construct than full-scale models.

A typical application example is determining the discharge capacity of a weir. In such cases, the entire geometry of the river is not replicated; instead, only a relevant area or the key parameters critical to the research question are modeled. Additionally, section models are often used for fundamental, schematic research questions where specific local conditions are not a factor.

Model family

A model family involves constructing the same experimental setup at multiple scales. Investigations across different scales make it possible to identify and quantify potential scaling errors. This helps improve the interpretation of results at the full natural scale.

While average flow velocities are typically well-represented in downscaled models, this is not always the case for turbulence parameters. A key reason for this discrepancy is the incorrect representation of the Reynolds number in scaled models. As a result, all processes dependent on the Reynolds number may be subject to errors.

The use of a model family provides a method to detect and estimate these scaling errors, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the results.

Fluid-Structure Interactions

The interaction of solid bodies with surrounding water falls under the category of fluid-structure interactions. Typical scenarios involving fluid-structure interactions include turbines, wind turbines, sediment transport, and the swimming behavior of aquatic organisms.

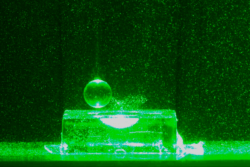

As part of fundamental research on the movement of sediment particles in water, experiments have been conducted to study the motion of individual particles using the 3D-PTV (Particle Tracking Velocimetry) technique. These investigations include studies on the flow structures at the initiation of motion for individual stones, as well as the flow conditions during collisions between stones.

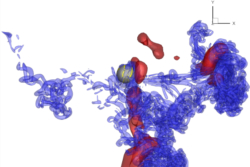

The results of these measurements not only contribute to a better understanding of the underlying physical processes but also support the development of new numerical methods for simulating the movement of stones.

Hybrid Modeling

Measurements are often limited in accuracy or can only be conducted at specific points. Many relevant physical quantities, such as pressure within the flow field, can only be measured indirectly. In cases where additional results for the entire three-dimensional domain are of interest, numerical simulations are employed. This combined approach is referred to as hybrid modeling.

In hybrid modeling, measured data are used to calibrate the numerical simulation. The simulations then provide data for the entire flow field. These data can, in turn, be used to refine the physical model experiment or to identify areas where additional measurements could yield new insights.

Another advantage of hybrid modeling becomes evident when changes to the geometry are required during the course of the experiments. While smaller changes are often easier to implement in physical model experiments, larger changes can be tested more efficiently in numerical simulations. This approach enables a flexible and precise investigation of complex flow and interaction processes.

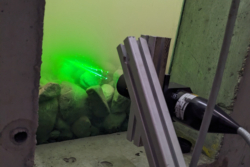

Laser Doppler Velocimetry – LDV

Laser Doppler Velocimetry (LDV) utilizes the Doppler effect by scattering laser light off small particles carried within the flow. From the frequency shift of the scattered light compared to the original laser beam, the velocity of the particles—and thus the flow velocity—can be determined.

This non-contact measurement technique allows for the precise determination of velocities at a single point with high temporal resolution. Due to these properties, LDV is not only suitable for measuring average flow parameters but is also highly effective for analyzing turbulence in flows.

Particle Image Velocimetry – PIV

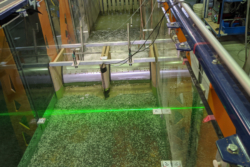

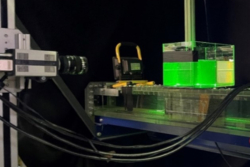

Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) is a non-contact, laser-optical measurement technique in which a plane of the flow is illuminated by a laser sheet. One or more synchronized cameras capture the motion of tracer particles within the illuminated plane at short time intervals.

By performing a correlation-based analysis of the characteristic displacement patterns of the particles between two consecutive images, velocity fields (velocity vectors) of the flow can be determined over larger areas. As an imaging technique, PIV is also highly suitable for visualizing flow fields.

3D Particle Tracking Velocimetry – 3D-PTV

3D Particle Tracking Velocimetry (3D-PTV) is based on the principle of Lagrangian particle tracking in three-dimensional space. By using multiple high-speed cameras from different viewing angles, the trajectories of individual tracer particles can be reconstructed with high temporal and spatial resolution.

From these particle trajectories, the velocity and acceleration of the particles are derived and interpolated onto a regular grid. This enables the detailed investigation of three-dimensional flows and fluid-structure interactions, making it a valuable tool in research areas where a deep understanding of flow dynamics is required.

Like Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV), this imaging technique can also be used to visualize flow fields. Laser-optical methods such as LDV, PIV, and 3D-PTV are advanced techniques for the precise measurement and analysis of flows in science and engineering.

Innovative Measuring Device Development – Color Classification in the Physical Model

To enable minimally invasive and efficient data collection in small- and large-scale model experiments, the continuous advancement of existing measurement technologies and the development of new, innovative, and non-contact measurement methods are essential.

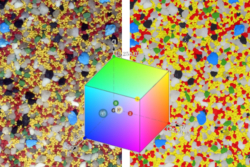

At the new hydraulic engineering laboratory at BOKU, dyed quartz sands and gravels are used to non-invasively capture the composition of the riverbed and the grain-size-dependent transport and dispersion patterns of sediments. These materials are recorded using high-resolution imaging, and color classification algorithms are applied to categorize them into groups of defined grain sizes.

Innovative Measuring Device Development – Intelligent Stones

To study the movement characteristics of transported stones in a flowing water body, the Institute for Hydraulic Engineering, Hydraulics, and River Research (IWA) employs “intelligent” stones. The new, large-scale models, including full-scale models, enable the use of state-of-the-art sensor technologies embedded within individual bedload particles. These “intelligent” stones allow for the continuous monitoring and characterization of immobile phases, mobilization, and transport. By measuring acceleration, angular velocity, and the surrounding magnetic field, combined with mathematical filtering techniques, the precise movement patterns of the stones can be analyzed.